|

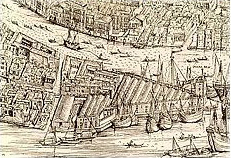

Venice before 1630

In the first decades of 17th century, from many points of view,

Venice was having some problems: economic (ruthless competition

from the French, English and Flemish merchants), political (alliance

with France, tension with Spain and even greater problems with the

Papacy, resulting in the Interdict) and military (the war against

the Uscocchi pirates for hegemony on the Adriatic and the war for

the succession of Mantua).

|

| |

Venice

began to take on a different role in the balance of European politics,

and was certainly more in the background than in previous centuries. Venice

began to take on a different role in the balance of European politics,

and was certainly more in the background than in previous centuries.

It is in this context that, 54 years after the terrible plague

of 1575-77, the disease gripped the city once more, taking tens

of thousands of victims. |

The plague As well as military defeat, the War of Mantua

brought Venice the plague.

The city found itself paralysed once again: traffic diminished,

the nobility took refuge in their country homes, and the population

was greatly reduced, roaming the city asking for charity.

Yet once again the government acted with decision and firmness:

it coordinated the disinfecting of the city, sequestered entire

neighbourhoods, set up the quarantine hospitals and buried the infected

dead under lime. Unfortunately, not even these sanitary measures

could halt the spread of the disease.

|

The quarantine hospitals In 1423 Venice became the first

state to have a special building for treating people with infectious

diseases. The island of S. Maria di Nazareth was chosen as the ideal

site for containing disease and guaranteeing isolation.

The isolation hospital was a place of both prevention and cure,

where the ill were treated and where much attention was paid to

separating the sick from the convalescents and the “suspected

ill”.

The birth of the quarantine hospitals is testimony to the Republic’s

revolutionary acts regarding hygiene.

|

Impotence

and superstition Impotence

and superstition The atmosphere in Venice was of dejection

and lack of faith. In this climate of fear it is easy to understand

the Venetians’ suspicion that the plague had been deliberately

caused by “plague-spreaders”.

Some French people were suspected of spreading the illness, but

this merely shows the Venetians’ psychological state after

succumbing to the terrible disease so soon after the epidemic of

the late 1500s.

It should be mentioned that Milan was ravaged by the plague during

the same period, as described by Manzoni in “The Betrothed”,

and there were trials against suspected plague-spreaders. At such

times there is always room for superstition and fanaticism.

|

The

vow The

vow In spite of strict sanitary measures the plague did

not seem to decline and so the Senate turned to divine help once

more.

On October 22, 1630, Doge Nicolò Contarini made a public

vow to erect a church called the Salute, asking for the Virgin Mary’s

divine intercession to rid the city of the plague. The first stone

was laid with the plague still raging through the city and the church

was consecrated in 1687. |

| The end of the plague

In November, 1631,

the plague was definitively eradicated, but at a terrible cost:

almost 47,000 died in the city (more than a quarter of the population)

and 95,000 in the so-called Dogado, comprising Murano, Malamocco

and Chioggia.

|

|