|

A city on water

The first description of the inhabitants on the lagoon comes from

the 6th century AD and was written by the Roman Cassiodoro:

| It appears as though you slide across fields with your

boats because from afar you cannot discern the canals from the

sandbanks... and whilst in other cities you tether animals to

the front of the house, you, with your houses of wicker and

reed, tether your boats. |

Even in those days, the city’s relationship with water was clear.

It is a relationship that has distinguished Venice and her inhabitants

ever since.

|

|

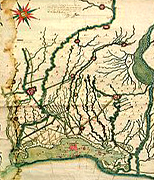

Since the beginning of its history, Venice has lived alongside water

and transformed it into its major sources of income: salt extraction,

fishing and river and maritime commercial traffic.

Over the centuries the city gradually extended its control of the

seas and the ensuing commerce. In fact, the Adriatic was known as

the Gulf of Venice.

|

|

| |

The city’s development brought with it a transformation in the

natural environment: in order to grow, the city needed to make living

space out of the water, orchards, fens, mud and sandbanks. More and

more land was reclaimed thanks to millions of poles driven into the

mud, which then became land to build on. An entire forest of upturned

trees lies at the base of the city. |

| |

The Venetians have always placed the utmost importance on water

and its regulation: for centuries they have controlled the flow

of rivers, even diverting their outlets to prevent the slow but

progressive flooding of the lagoon. Over the centuries, the flow

of the Brenta, Dese, Sile and Piave rivers has undergone substantial

diversions to allow Venice and its lagoon to survive.

Great attention was given to providing drinking water and its use

was regulated by specially formed magistrates. |

|

A city of rowers

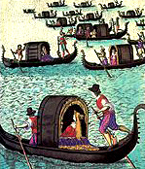

Venice was, and to an extent still is, a city whose principal means

of communication consisted of canals and the traffic was on water.

Venice was, and to an extent still is, a city whose principal means

of communication consisted of canals and the traffic was on water.

Rowing everywhere is a centuries-old form of transport and continues

to survive to this day. Centuries ago, rowing was the ideal training

for mariners working for the Venetian military and civil fleet and

was indispensable for all Venetians.

All the patrician palaces had an entrance opening onto the street

and another more important and magnificent one opening onto the

canal. This is where gondolas were moored, ready to take their masters

and guests around the city.

|

| Venetian-style rowing As they travelled by boat

or ship, Venetians became able seamen and rowers, and were experts

in understanding winds, currents and tides.

The

surrounding environment forged and conditioned the methods of navigation

and lagoon rowing. The

surrounding environment forged and conditioned the methods of navigation

and lagoon rowing.

The shallow seabed, the winding canals and the presence of sandbanks

called for flat-bottomed boats without a keel. The need for maximum

visibility to locate the most navigable routes led to stand-up rowing,

while the need for using just one oar through the narrow city canals

saw the creation of asymmetric boats that enabled this kind of rowing.

The need to freely move the oar in order to push down on the shallow

seabed or to slip down narrow canals led to the creation of an open

rowlock, the forcola. For the same reasons, the rudder was also

abandoned and substituted by the oar.

|

| Gondoliers  Before

becoming a category exclusively dedicated to tourism, the gondoliers

were the spirit of the city, acting as oar-wielding chauffeurs. Before

becoming a category exclusively dedicated to tourism, the gondoliers

were the spirit of the city, acting as oar-wielding chauffeurs.

They either worked for a patrician family or were employed in public

service and were available to anyone who wanted to reach any part

of the city or lagoon.

This category, which was to become the very symbol of the city,

for centuries constituted the heart of the spectacular regattas

that were increasingly being organised in the city.

|

| Birth of the Regata

The

regata or rowing race is the most specifically Venetian of local

competitive events and has always exerted considerable appeal for

both Venetians and visitors. The

regata or rowing race is the most specifically Venetian of local

competitive events and has always exerted considerable appeal for

both Venetians and visitors.

The earliest historical evidence relates the races to the celebrations

surrounding the festival of the Marys and date from the second half

of the 13th Century. However, it is probable that similar events

were already popular: Venice was essentially a seafaring city and

ready reserves of expert oarsmen were a prime necessity.

The etymology of the term regata is uncertain. Some trace it to

the word riga (line), others to the verb aurigare

(to compete in a race); and others again to ramigium (rowing);

in any case, the Venetian term regata entered the main

European languages to denote a competitive event raced in boats.

During the Renaissance regate were organized mainly by the Compagnie

della Calza (associations of young noblemen) but from the mid-16th

Century, the Venetian government appointed specific noblemen - called

direttori di regata - to arrange and supervise the races.

|

The competition

A

typical regatta has always comprised various races using different

kinds of boats and on the occasion of a regatta, the Lagoon in front

of St. Mark’s and the Grand Canal is always teeming with decorated

craft of all kinds, full of passionately keen spectators. A

typical regatta has always comprised various races using different

kinds of boats and on the occasion of a regatta, the Lagoon in front

of St. Mark’s and the Grand Canal is always teeming with decorated

craft of all kinds, full of passionately keen spectators.

To clear the course of the race and to keep order, the regatta used

to be preceded by a fleet of bissone, typical long boats

containing noblemen standing in the bows and armed with bows. Their

job was to pelt the more unruly of the spectators with terracotta

shot. Now the bissone still head the procession before the races,

but they no longer perform a disciplinary function.

The Regata Storica as we know it now, with its commemorative cortege

acting as a prelude to the competitions, was conceived at the end

of the 19th century for the 3rd Biennale d'Arte as a way of offering

another tourist attraction. |

Famous regattas

Regate were more common in the past than now and were of two main

types: challenge events between boatmen or gondoliers and regate

grandi, organized as part of the celebrations for some religious

or civic occasion.

For centuries, the regata was also a customary way of marking the

accession of a new Doge and Dogaressa, the appointment of important

public officials such as the Procuratori di San Marco and of welcoming

distinguished visitors to the Serenissima Republic. Dignitaries

honoured in this way included Beatrice d’Este in 1493, Anna

de Foix, Queen of Hungary in 1502, Henry III of France in 1574,

Frederick IX of Denmark in 1709 and the Crown Prince and Princess

of Russia in 1782.

Not infrequently they were also organized and financed by foreign

princes, a famous example being the regata of 1686, arranged at

the wish of Duke Ernest August of Brunswick, a general who had fought

bravely in the service of the Serenissima. |

|